Nothing heralds the holiday season like the Christmas tree, but did you know that most of Hawaiʻiʻs Christmas trees are…

Read More

Kia'i Moku Column

Gobble Gobble! Maui’s Wild Turkeys

With Thanksgiving only 12 days away, the traditional centerpiece of this holiday meal is likely on your mind. Stores will…

Read More

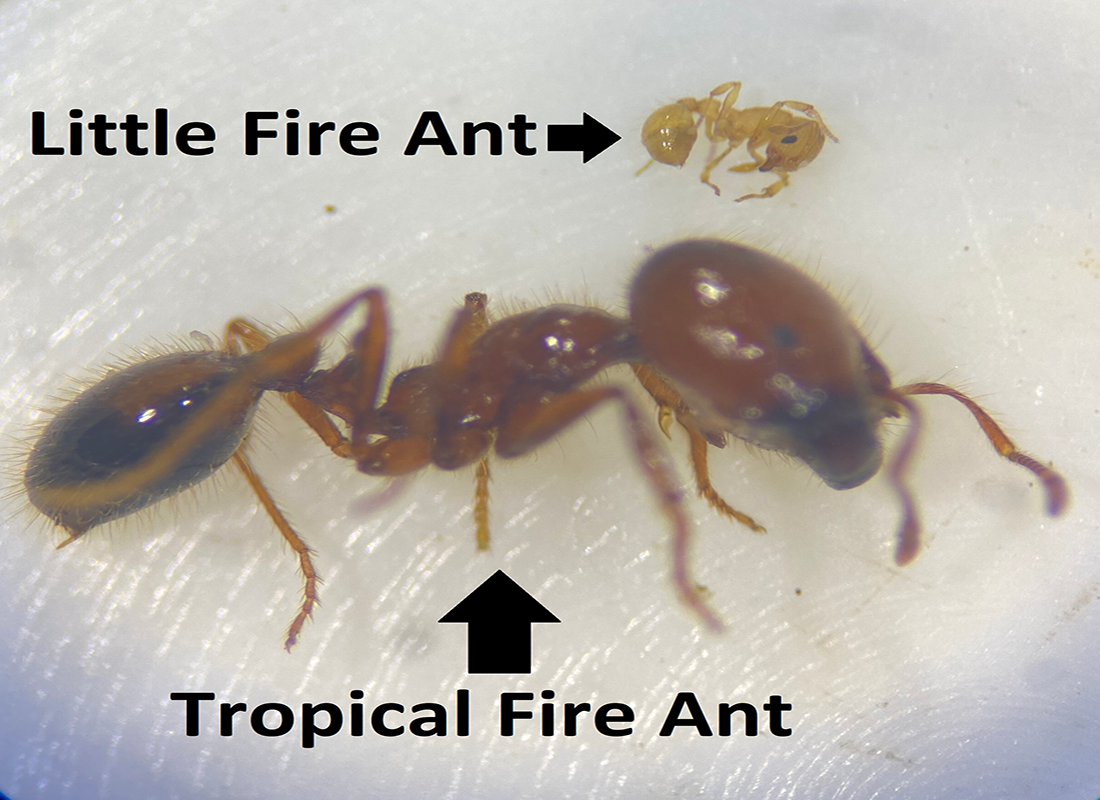

Not All Fire Ants Are The Same

It’s a familiar feeling many of us have experienced. You may have been picnicking in a park, loading up a…

Read More

Be like Bob: The Importance of Reporting Something Out of Place

Retired state forester Bob Hobdy knows his trees. So, when he was driving through his Haʻikū neighborhood earlier this summer…

Read More

Keep an eye out for invasive parakeet

In July 2021, a Kīhei resident reported a strange-looking bird near their condo to the State-wide online pest reporting system,…

Read More

Coffee Leaf Rust Never Sleeps

You may be holding a cup of it now as you read this. Warm and comforting, coffee is the fuel…

Read More