Back in 2009, a father and his two kids, still wet from the beach, walked into the office of the…

Read More

ʻŌhiʻa’s genetic diversity may contribute to disease resistance

ʻŌhiʻa is both a pioneer – the first to grow on new lava– and a protector—hosting and sustaining birds, insects,…

Read More

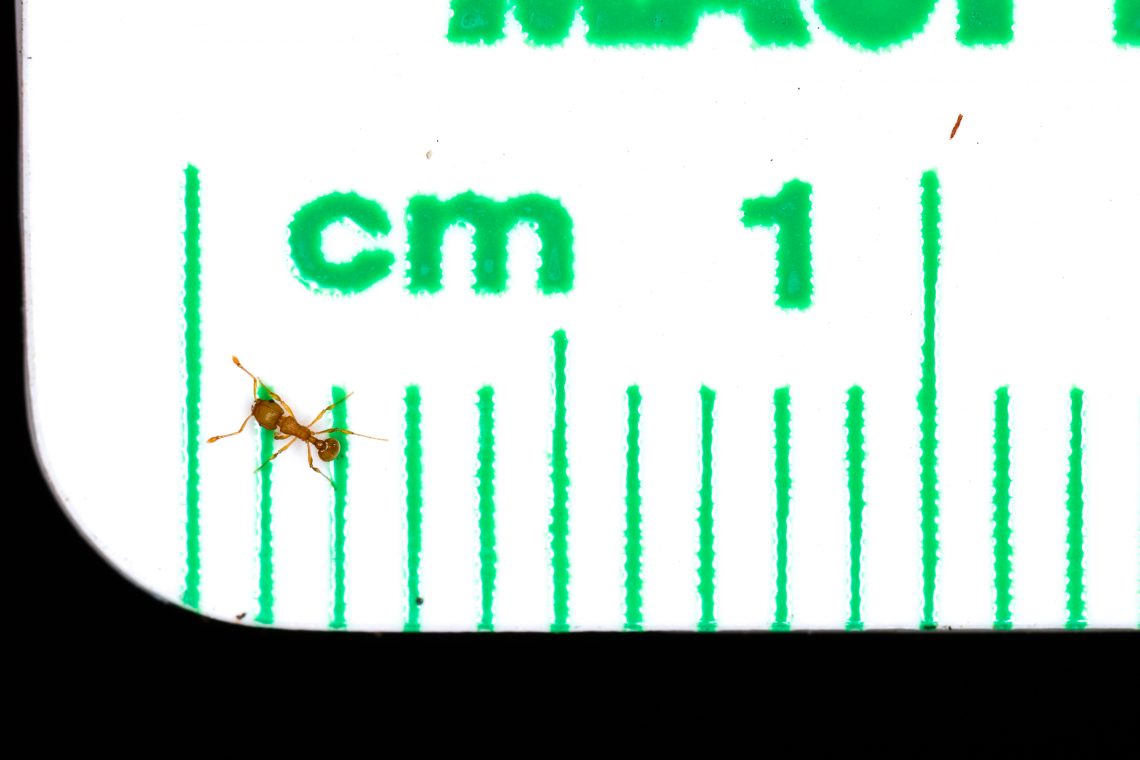

Press Release: Haʻikū residents report stinging ants, uncovering a small population of invasive little fire ants

Date: November 19, 2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASEContact: Lissa Strohecker, Public Relations and Educational Specialist Maui Invasive Species Committee PH: (808)…

Read More

Plant Crew – September 2020

Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death response: In response to community reports, Mike Ade collected two samples for possible Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death: one…

Read More

Molokai/Maui Invasive Species Committee -September 2020

The Molokai Crew at MoMISC has been working hard to continue their surveys for early detection species including little fire…

Read More