Five years ago, people living in the Puna district on Hawaiʻi Island started seeing native ʻōhiʻatrees in their yards dying….

Read More

Home-Featured

Look closely—the endemic insects of Haleakalā

The flightless moth of Haleakalā is one of the more dramatic examples of evolution in Hawaiian insects. Known to science…

Read More

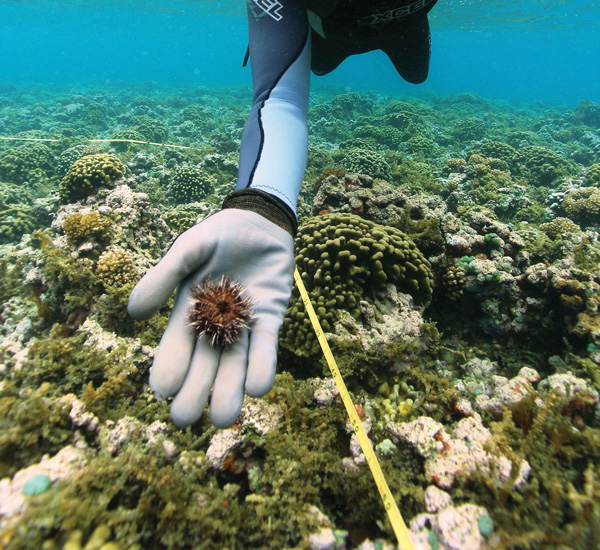

Roomba on the Reef–Native collector urchins on the prowl for invasive algae

Let’s say you are trying to remove tiny piece of invasive plant material from an area 8 miles long and…

Read More

Premiere of the new documentary Invasion: Little Fire Ants in Hawaii

In 2009, Waihee farmer Christina Chang was stung on the eye by a tiny ant at her home on Maui….

Read More

And then the pollinator wasp arrived…

Lori Buchanan, manager of Moloka‘i/Maui Invasive Species Committee (MoMISC), was in downtown Kaunakakai recently when she saw something strange sprouting…

Read More