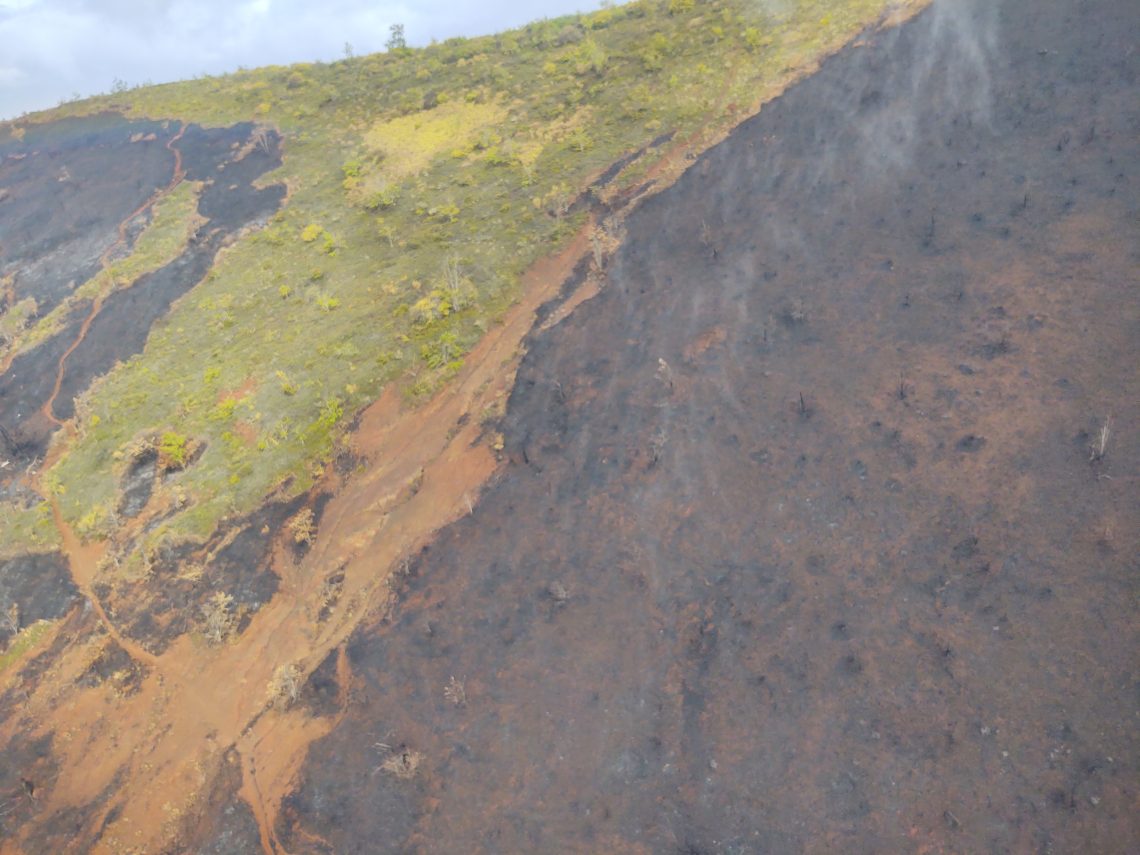

In early November, a wildfire ripped through nearly 2,100 acres of parched land in West Maui. The fire blazed across…

Read More

Kia'i Moku Column

The Sweet History of ʻUala: A Staple Food to Give Thanks For

A year-round staple in our islands will soon take center stage on many Thanksgiving dessert tables. The sweet potato is…

Read More

Citizen Science Can Help Stop the Ant

Citizen scientists have been key to finding most of the little fire ant (LFA) populations on Maui. Without their reports,…

Read More

New training helps nurseries be on the lookout for invasive species

Hawaiʻi is home to plant and animal species found nowhere else. For millions of years, new arrivals would establish in…

Read More

The Hawaiian Crow May Soon Soar on Maui

One of the rarest birds in the world may soon fly through the remote, forested slopes of Maui. The ʻalalā,…

Read More

New rabbit disease discovered on Maui

In June of 2022, the Hawaiʻi Department of Agriculture (HDOA) alerted the public that tissues submitted by a practicing Maui…

Read More