Kevin Gavagan, Assistant Director of Engineering at Four Seasons Resort Maui at Wailea, is the 2022 recipient of the Mālama…

Read More

2022

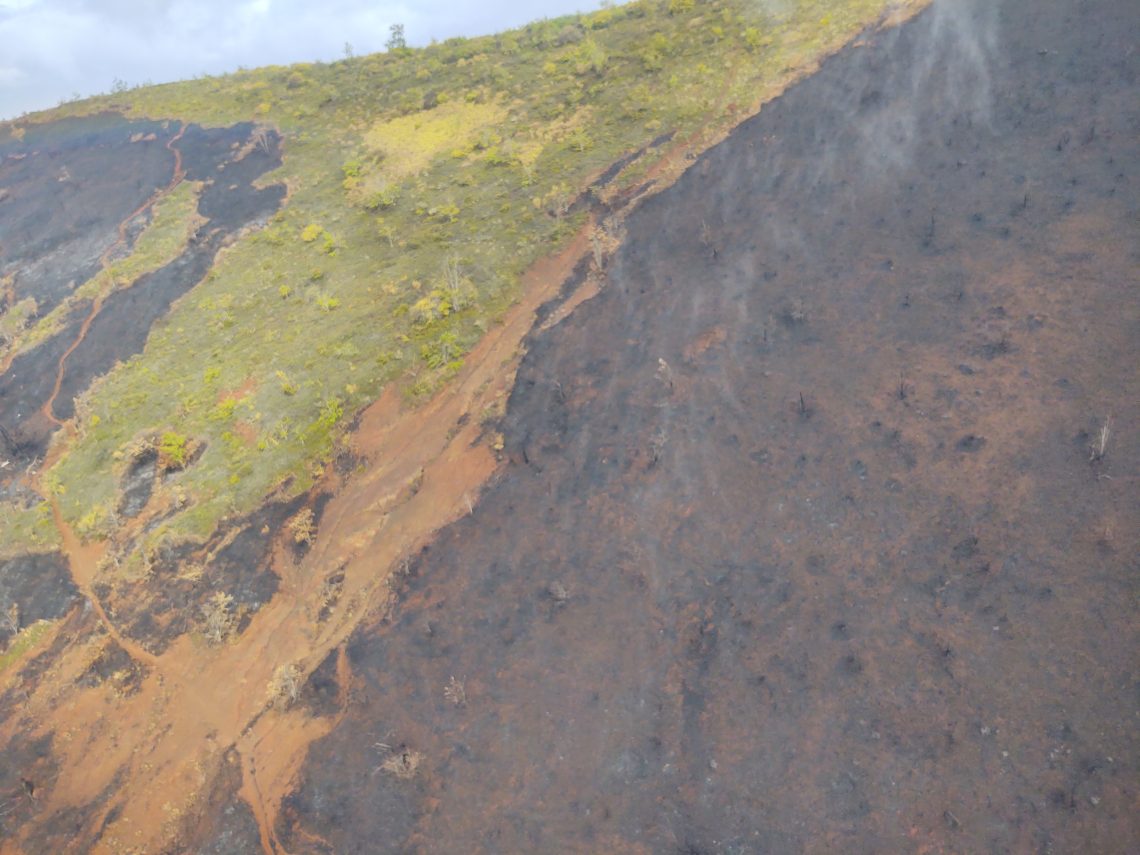

Invasive species can cause native ecosystems to go up in smoke

In early November, a wildfire ripped through nearly 2,100 acres of parched land in West Maui. The fire blazed across…

Read More

The Sweet History of ʻUala: A Staple Food to Give Thanks For

A year-round staple in our islands will soon take center stage on many Thanksgiving dessert tables. The sweet potato is…

Read More

Citizen Science Can Help Stop the Ant

Citizen scientists have been key to finding most of the little fire ant (LFA) populations on Maui. Without their reports,…

Read More

New training helps nurseries be on the lookout for invasive species

Hawaiʻi is home to plant and animal species found nowhere else. For millions of years, new arrivals would establish in…

Read More