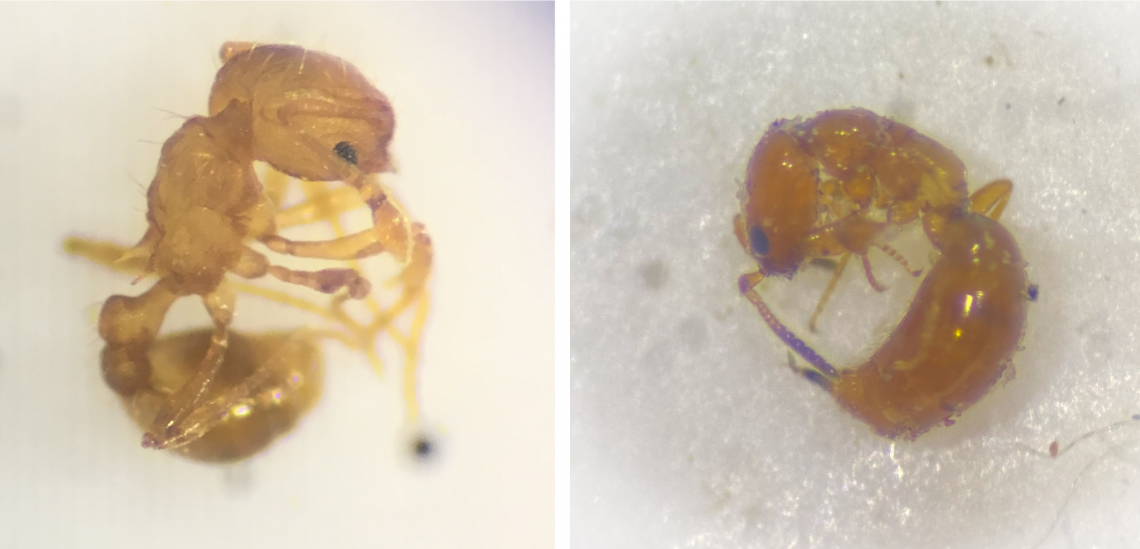

In March of this year, a Lahaina couple reported a stinging but slow-moving, tiny ant- armed with a large stinger…

Read More

Kia'i Moku Column

Protecting Māmaki From Invasive Species

The Kamehameha butterfly, the state insect of Hawaiʻi, is found nowhere else in the world and neither is the plant…

Read More

Celebrating Native Hawaiian Plant Month

Hawaiʻi is the most isolated landmass on the planet. Because of this, plants and animals that arrived here millions of…

Read More

643PEST simplifies reporting invasive species throughout Hawai’i

In the late 1990s, a Maui-based ecologist and scientist working with the US Geological Survey (USGS) envisioned a simple, straightforward…

Read More

Evolutionary oddities: giant flightless ducks roamed Maui, grazing like buffalo and spreading seeds

For millennia, before humans ever set foot on Hawaiʻi, birds ruled the islands. From mountain top to shoreline, the feathered…

Read More

Earthworms: an invasive species underfoot in Hawai’i

If you garden, you’ve gained an appreciation for the relationship between soil and plant health. From soil pH to mineral…

Read More