Kevin Gavagan, Assistant Director of Engineering at Four Seasons Resort Maui at Wailea, is the 2022 recipient of the Mālama…

Read More

Duane Sparkman Receives 2021 Mālama i ka ʻĀina Award

Duane Sparkman, Chief Engineer at the Westin Maui Resort and Spa, is the 2021 recipient of the Mālama i ka…

Read More

The race to protect Hawaii’s native forest birds from extinction

The upland realm of wao akua captivates all senses. Freshwater percolates into the earth, perfuming the cool air, and hues…

Read More

Prevention Is Key For Maui To Stay Coconut Rhinoceros Beetle Free

A large, invasive beetle is spreading on Oʻahu. First detected in December 2013 at a golf course near the Honolulu…

Read More

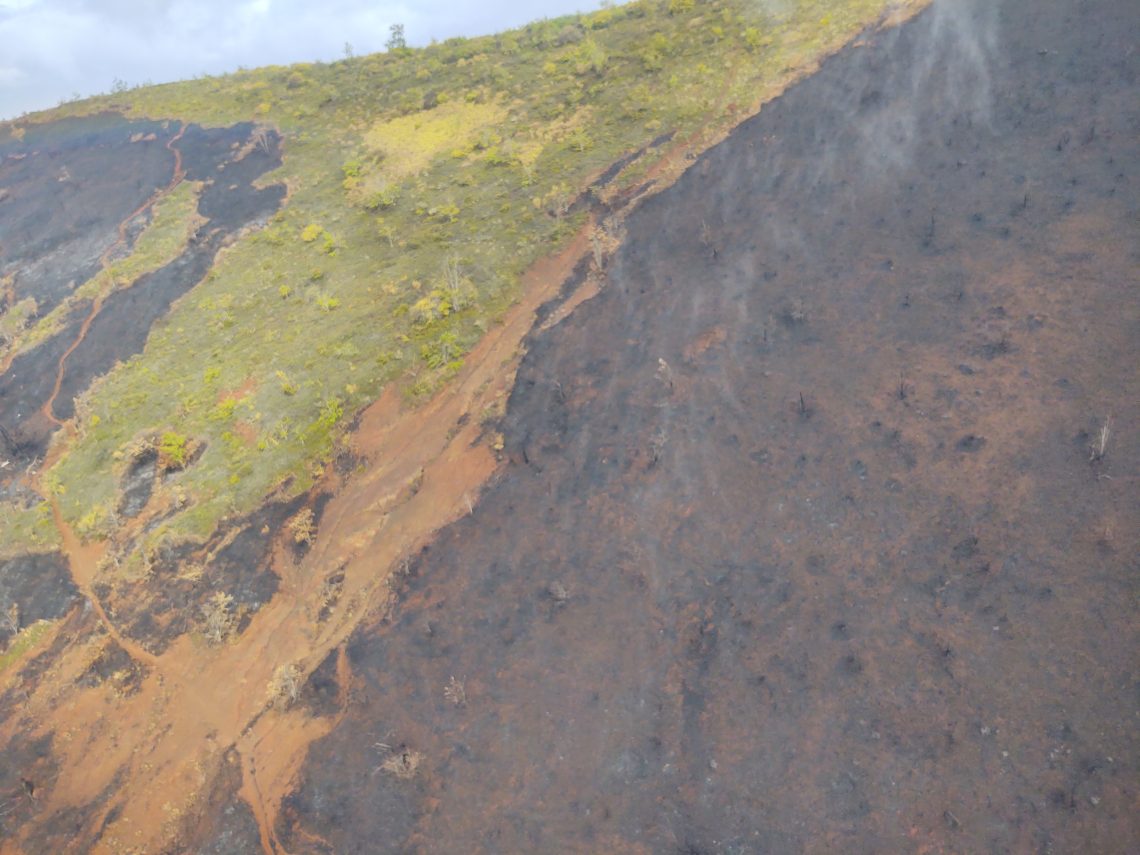

Invasive species can cause native ecosystems to go up in smoke

In early November, a wildfire ripped through nearly 2,100 acres of parched land in West Maui. The fire blazed across…

Read More