With 75% of detections coming from residents, community engagement continues to be the key to protection. The Maui Invasive Species…

Read More

MISC Target Species

Coqui Update: December 2024

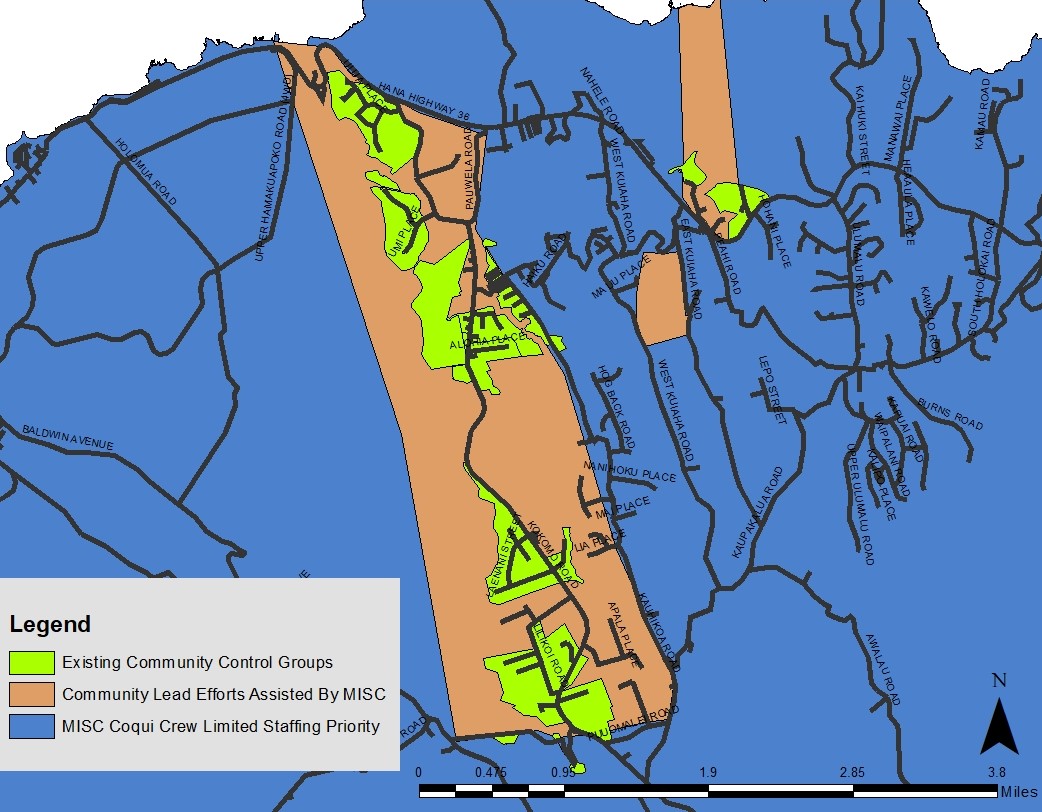

Coqui are primarily limited to a six-square mile area of Haʻikū and we are not giving up. Our goal is to empower communities to manage coqui locally and prevent new populations from spreading.

With your support, we can make a difference. Mahalo nui loa for your kōkua and patience as we navigate these challenges. Together, we can continue protecting Maui from invasive species.

Coqui Staffing Update: October 2024

Maui is 735 square miles; coqui are established in various densities across roughly six square miles. Current staffing prioritizes response to coqui…

Read More

Trace-forward reveals little fire ants in Kīpahulu. Public encouraged to report stinging ants

On August 26th, 2024, the Maui Invasive Species Committee (MISC) field crew detected a small population of little fire ants…

Read More

Press Release: New invasive little fire ant population discovered in Huelo

PRESS RELEASE Date: June 3, 2021 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASESubject: New invasive little fire ant population discovered in HueloContact: Serena Fukushima,…

Read More

Research informs the efforts to stop Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death (ROD)

ʻŌhiʻa are the pioneers – the first trees to grow on bare lava. ʻŌhiʻa are also adaptable – they grow…

Read More