The Aedes aegypti mosquito is the primary vector of dengue worldwide. This species is not widespread in Hawaii. Photo by James Gathany,CDC.

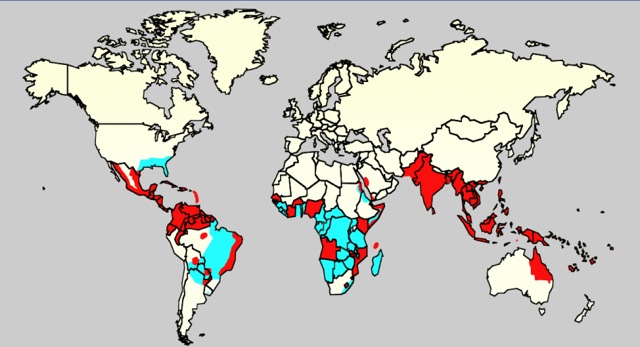

The news is abuzz with mosquitoes these days; outbreaks of dengue fever on Hawaiʻi Island have us all a little more nervous when the high-pitched whine of a tiny pest reaches our ear. Mosquito-vectored viruses like Zika and chikungunya are on the horizon. Health officials in both South America and Hawaiʻi Island are scrambling to find ways to reduce mosquito populations and protect human health. Scientists are busy making nearly daily advances in the lab as well. All of the energy focused on removing these pests raises the question: how would the total removal of mosquitoes alter ecosystems?

There are over 3,500 species of mosquitoes in the world, of which only a few hundred bite. Mosquitoes and their larvae are food for fish, bats, birds, and dragonflies. Male mosquitoes don’t suck blood, they daintily sip nectar. In return, they help to pollinate some aquatic plants. But despite their service as prey and pollinator, many scientists think ecosystems would recover just fine if mosquitoes were gone–other insects could fill that niche, and we’d have one less vector for disease. Good news globally, but it only gets better for Hawaiʻi.

The Culex mosquito, larvae shown here, is the mosquito responsible for spreading avian malaria between introduced and native birds. Photo by James Gathany, CDC.

In Hawaiʻi, mosquitoes are food for native bats (ʻōpeʻapeʻa) and dragonflies (pinao). Would these species go hungry without this imported food source? Not in the least, explains Dennis Lapointe, an ecologist with the US Geological Survey who researches the ecological role of mosquitoes and birds in Hawaiʻi. “[Mosquitoes] are all non-native and everything that is native and endemic got along fine without them.” Some species of native damselfly larvae eat mosquito larvae, but they have other food sources.

The greatest ecological benefit would be to our native birds. Disease-spreading mosquitoes are a significant factor keeping iʻiwi,ʻ apapane, and other Hawaiian honeycreepers from flitting through the trees in your yard.

Aedes albopictus is widespread in Hawai’i and is a vector of Zika among other human diseases. Photo by James Gathany, CDC.

Mosquitoes first arrived in Hawaiʻi when sailors dumped a barrel of water containing larvae of the Culex mosquito into the wetlands that once surrounded Lahaina. The Culex mosquito became the vector that spread avian pox and malaria from non-native birds to Hawaiian forest birds, precipitating their decline. The native passerines lacked any resistance against these foreign diseases.

Today, our few remaining native forest birds are relegated to high-elevation refuges, protected by temperatures cool enough to keep mosquitos at bay. But protection could be short lived; current estimates of climate change indicate these refugia could disappear within 80-100 years.

If mosquitoes disappeared, so would the threat of avian malaria.

Currently, the fate of native birds is not foremost in our minds as human-health threats loom: the Aedes mosquitoes, which are also found in Hawaiʻi, are in the news now. A. albopictus, widespread throughout the Islands, is the primary carrier the Zika virus. A. aegypti, a mosquito found only in a few areas on Hawaiʻi Island, is the optimum carrier of dengue. Both Aedes species carry chikungunya. Both of these mosquitoes cause harm, with negligible environmental benefit.

Meanwhile, scientists are working on a tool to reduce mosquito populations without pesticides. Using genetic technology, a self-limiting gene is inserted into the DNA of male mosquitos. Reared in labs, the mosquitos are released to seek out and mate with females, but the self –limiting genes is passed along and their offspring die as

Mosquitoes breed in standing water, and removing breeding sites is one way to help reduce the density of mosquitoes. Photo by Mary Hollinger, NOAA.

larvae. The existing adults die off and are not replaced. Though years from being ready for release into the wild, scientists predict that these altered mosquitoes could be up to 99 percent effective in reducing mosquito populations, with no risk of developing resistance to pesticides. Each species of mosquito has to be targeted specifically, but Hawaiʻi has only a handful of invasive mosquitoes, all of which are non-native.

It’s something to think about: Hawaiʻi without mosquitoes, without the threat of dengue, Zika, or chikungunya. And, as an added benefit, Hawaiian forests with a few more native birds.

Until then, continue with mosquito-control efforts: dump standing water, treat bromeliads and other plants that hold water and mosquito larvae, and regularly apply repellent. These actions can help keep these blood-suckers at bay in your backyard.

Read more:

- Eliminate mosquito breeding sites: https://health.hawaii.gov/docd/files/2017/01/Eliminate-Mosquito-Breeding-Sites.pdf

- Ecological role of mosquitoes: www.nature.com/news/2010/100721/full/466432a.html

- Avian diseases in Hawaiʻi: https://mauiforestbirds.org/avian-disease/

Kia’i Moku, “Guarding the Island,” is prepared by the Maui Invasive Species Committee to provide information on protecting the island from invasive plants and animals that can threaten the island’s environment, economy and quality of life.

Written by Lissa Strohecker. Originally published in the Maui News on February 14th, 2016 as part of the Kia‘i Moku Column from the Maui Invasive Species Committee.