Date: August 6, 2021

Subject: New Invasive Species Alert: Rose-ringed Parakeets Found on Maui

Contact: Serena Fukushima, Public Relations and Educational Specialist

Maui Invasive Species Committee

PH: (808) 344-2756

Email: miscpr@hawaii.edu

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Rose-ringed parakeets (RRP) have recently been confirmed on Maui. An interagency effort between the Maui Invasive Species Committee, Hawaii Department of Agriculture, Department of Land and Natural Resources Division of Forestry and Wildlife, Maui Nui Seabird Recovery Project, and Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project has led to one bird being captured in Kihei as a result of an online report to www.643PEST.org, a reporting resource made available by the Hawaii Invasive Species Council. At least four more birds remain at large in West Maui. These four birds were reported by a Napili resident who observed them frequenting a bird feeder. Follow-up visits by staff from the Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project confirmed their presence. Efforts were made to capture these remaining birds on July 30; however, the birds were not observed and are assumed to have moved on to another feeding location.

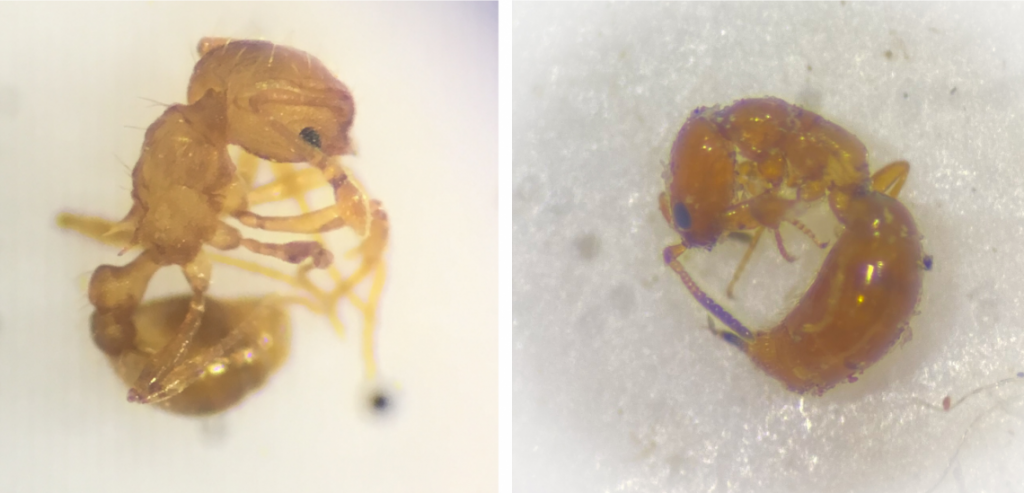

Not to be confused with the Rosy-faced Lovebird, which is already established on Maui, Rose-ringed parakeets are native to equatorial Africa and Asia and have invasive populations in over 35 countries. There are established populations of RRP on Oʻahu, Hawaiʻi Island, and Kauaʻi. They are an agricultural pest that causes extensive damage to food crops, especially fruits and grains. On Kauaʻi, they have already successfully invaded farmland and have caused significant losses to harvests. Their high-density roosts, loud calls, and mass accumulation of droppings cause disturbance to humans and are a potential public health risk. If they reach native forests, their impact on native ecosystems could be substantial. The most recent population estimate of Kauaʻi RRP numbers is over 10,000 individual birds, with the rate of expansion steadily climbing along with costs to control them. The Kauai Invasive Species Committee, in partnership with the Rose-ringed Parakeet Working Group, is conducting research to develop management methods to mitigate these harmful pests.

MISC is asking the Maui community to help in early detection efforts by reporting any sightings of these few remaining birds. Report any sighting of Rose-ringed Parakeets on Maui to www.643pest.org or call (808) 643-PEST (7378). Questions may be directed to miscpr@hawaii.edu.

MISC appreciates your support in the rapid response effort to keep Maui free of this invasive species!