Click this link for a PDF version of the newsletter: 2012 MISC Newsletter Kia’i i na Moku o Maui Nui

Click this link for a PDF version of the newsletter: 2012 MISC Newsletter Kia’i i na Moku o Maui Nui

In this issue:

Moeana Besa and her family live in a part of Tahiti plagued by little fire ants. Photo by Masako Cordray

Moeana’s Message―What Tahiti Can Teach us about Little Fire Ants

“This place used to be paradise” said Moeana Besa. Find out what happened.

On Page 1

Fire at the Farm

How Christina Chang helped stop the establishment of the little fire ant on Maui.

On Page 3

On the Job

Where can you find a snake handler, exploratory entomologist, educator, advocate, law enforcer, pesticide applicator examiner, irrigation specialist, and ant wrangler? Try the Hawaii Department of Agriculture.

On Page 5

New Science

Paintball guns, scuba tanks, and spacklers—the promising new techniques for treating little fire ants.

On Page 6 (check out the video of the spackler in action!)

Tiny Ants, Huge Nuisance

Learn more about the little fire ant and why this wee creature is such a big problem

Learn more about the little fire ant and why this wee creature is such a big problem

On Page 6

Education Saves the Day!

How a class visit led to the detection of the little fire ant on Maui.

On Page 9

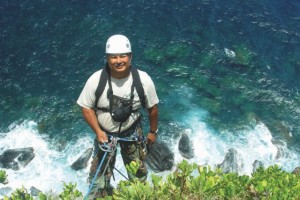

MISC field crew leader Darrell Aquino is up for any challenge

Dauntless Darrell

The keen eye of Darrell Aquino, pig hunter and dedicated MISC employee.

On Page 10

PLUS:

- MISCommunication-The Comics of Brooke Mahnken

- Managers Corner

- Is that fire ant Little? Tropical? or Red Imported? Dr. MISCellaneous knows the difference!