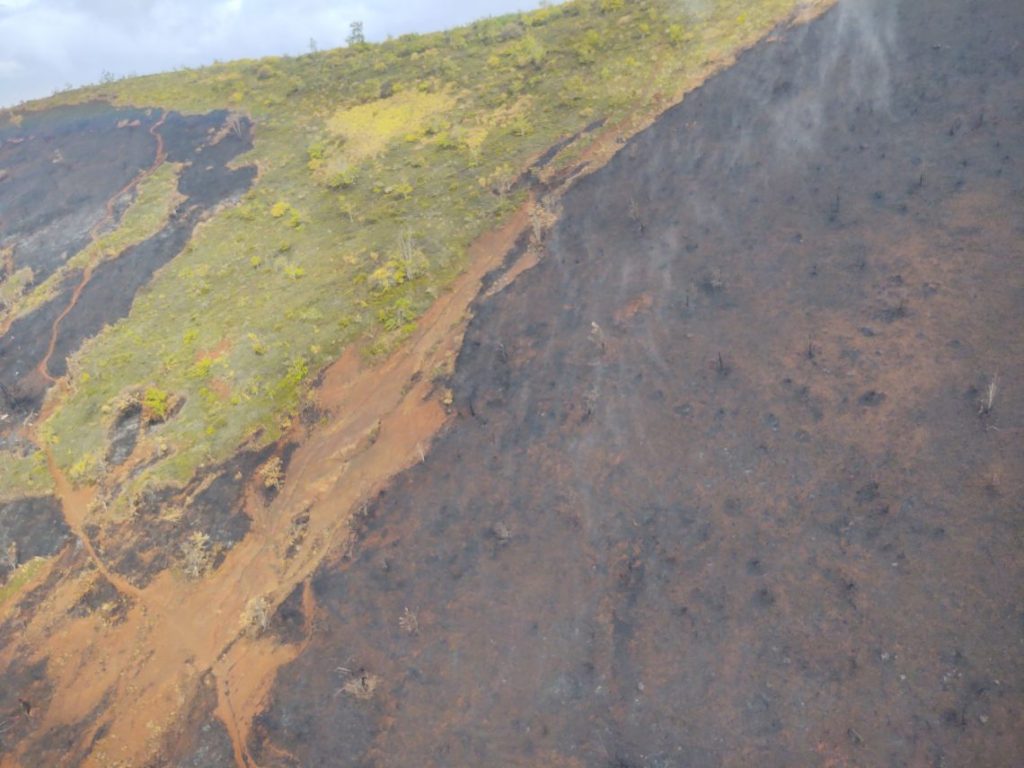

After the brush is cleared, contractors build the barrier fence. This section is one of the first completed on what will eventually become three miles of barrier built along the eastern side of Māliko Gulch.

In the summer of 2023, Ha‘ikū homeowner Carole Harris decided she’d had enough. For two years she had spent almost every night catching coqui in her yard. It was only two or three butcher knew what would happen if she wasn’t vigilant. Her neighbor didn’t control coqui and Harris, like many others, found the piercing call intolerable. “I had to be out there as soon as I heard them,” she said. She decided to invest in a barrier to keep coqui out of her yard.

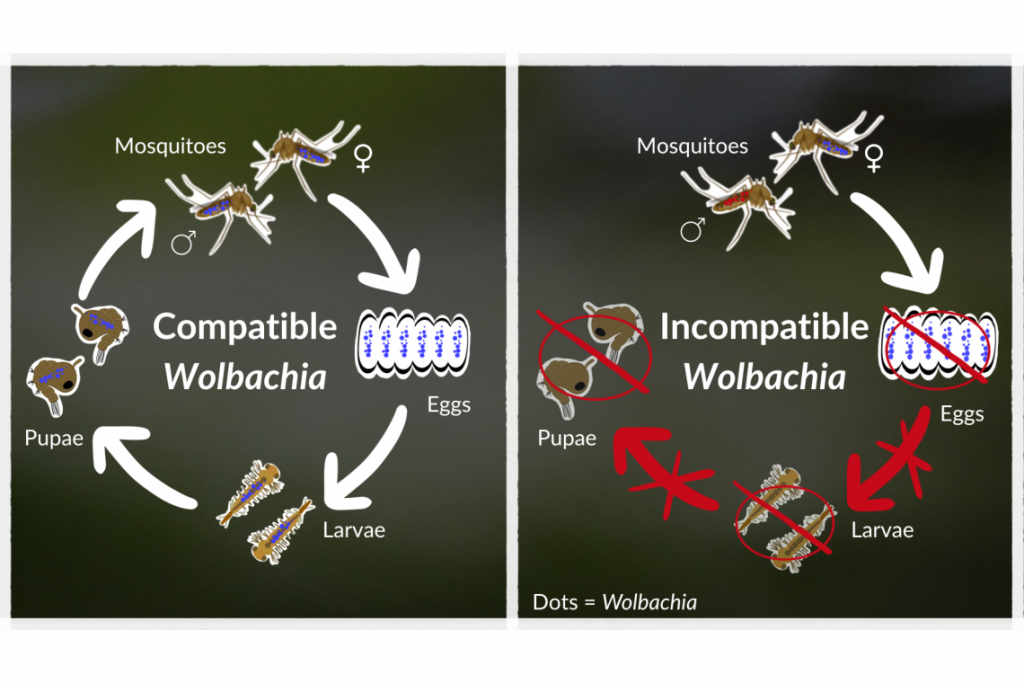

Coqui barriers were first developed and tested by the University of Hawai‘i – College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources on Hawai‘i Island to help nursery owners keep coqui frogs from getting into their greenhouses. Coqui frogs can’t hold on upside down; so faced with a fence that had an overhang of 90 degrees, even the Alex Honnold of coqui couldn’t climb over.

Harris ordered some landscape fabric and got to work. She’s happy with the outcome; “I haven’t had a frog in my yard for months,” she said. A handful of other Ha‘ikū residents have built barriers around their properties and they’re a common feature of Hawai‘i Island greenhouses.

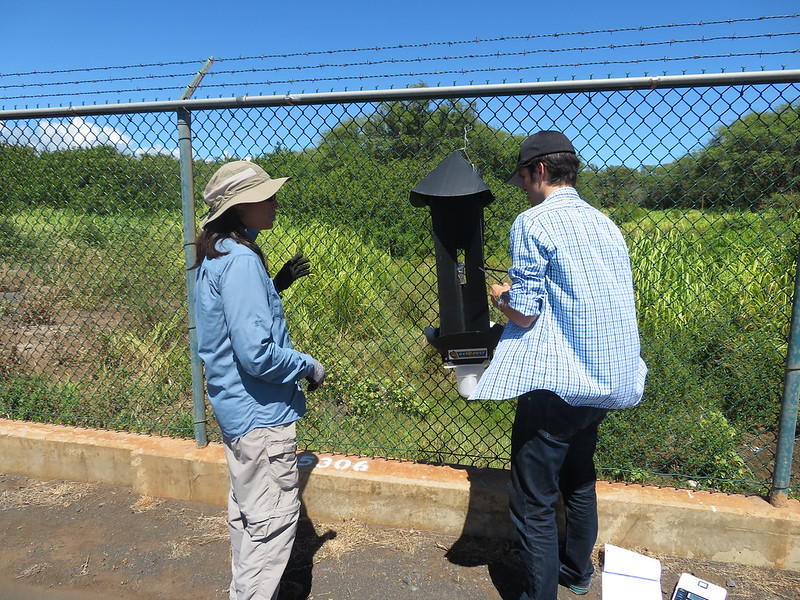

The Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources Division of Forestry and Wildlife (DoFAW) and the Maui Invasive Species Committee (MISC) are hoping these successes translate to a landscape scale. In October, contractors begin building a barrier along the eastern sections of Māliko Gulch. DoFAW funded the project, MISC is working with the community on placement. “Our goal is that it will provide ongoing passive suppression, limiting the movement of coqui into neighborhoods,” explains Matt Cook of MISC. He’s responsible for coordinating access with property owners for barrier construction.

Once completed, the barrier will limit the spread of frogs along three miles of the gulch. Cook has been working with nearly 50 property owners. Like any landscape-level fencing effort, terrain is the most significant factor influencing where the fencing will go. Small but steep “finger” gulches can’t be efficiently fenced. Priority areas for fencing are those sections where coqui are known to enter neighborhoods.

Barrier construction will take several years. Before the barrier can go up, any existing brush has to be removed on 20 feet of either side of the fence line so it doesn’t provide a springboard for coqui or fall on the barrier and destroy it. Once the barrier is built, MISC will be working with the property owners to maintain both the vegetation buffer and the fencing material going forward.

Like sandbags along an overflowing river, the final barrier will limit where coqui can spill out of Māliko Gulch. Megan Archibald, Coqui Coordinator, sees how the barrier will complement coqui control in the rest of Ha‘ikū. “We’ll be better able to anticipate where coqui is moving and focus the crews’ effort on those gulches and steep terrain,” she says. But the greatest impact will be on the neighbors who’ve been working together to control coqui in their backyards. “Hopefully, the neighborhood spray programs will have a greater impact if coqui can’t reinvade as quickly,” Fewer coqui in neighborhoods means a lower risk of coqui hitchhiking to the rest of Maui.

To learn more about the efforts to control coqui frogs on Maui, visit mauiinvasive.org

Lissa Strohecker is the public relations and education specialist for the Maui Invasive Species Committee. She holds a biological sciences degree from Montana State University. Kia’i Moku, “Guarding the Island,” is prepared by the Maui Invasive Species Committee to provide information on protecting the island from invasive plants and animals that can threaten the island’s environment, economy and quality of life.

This article was originally published in the Maui News on December 9, 2023, as part of the Kia‘i Moku Column from the Maui Invasive Species Committee.

Read more Kiaʻi Moku articles