Knowing what to plant and where can be tricky. Planting guides from the Hawaiian moon calendar to publications from the University of Hawaiʻi’s Cooperative Extension Service all help. They offer information and guidance on proper soil conditions and sun requirements, but did you know that along with these great resources, there are also tools and guides to help ensure that the plants themselves are pono?

Programs offered for growers and nurseries through Plant Pono can do just that. Plant Pono is a partnership between the Coordinating Group on Alien Pest Species, the Hawaiʻi Invasive Species Council, and the Landscape Industry Council of Hawaiʻi.

First, there’s the Plant Pono Endorsement Program. The program relies on the Hawaiʻi Pacific Weed Risk Assessment (HPWRA). HPWRA is an evaluation of a plant’s potential to become invasive and cause harm in Hawaiʻi. An assessor with the HPWRA looks at the characteristics of a plant – from growing requirements to the number of seeds it produces – and takes into consideration the conditions present in Hawaiʻi -from pollinators to potential predators–to predict the plant’s potential to be invasive. The final result is a guideline for growers and gardeners indicating whether the plant has a low, moderate, or high risk of causing harm.

Businesses endorsed through the program have pledged to use plants that won’t become invasive. By voluntarily choosing to not sell high-risk plants, these businesses are demonstrating their commitment to Hawaiʻi and providing plants that won’t displace native species. At this time, the Pono Endorsement Program is only located on Hawaiʻi Island and Kauaʻi.

If you are not living on an island with a Pono Endorsement Program, the plantpono.org website is a great resource for both nurseries and consumers to look up if a plant is pono or not. With over a thousand plants listed in its database, it’s easy search tool helps to quickly find the perfect fit for your garden or landscape that will also not pose a threat to our greater environment.

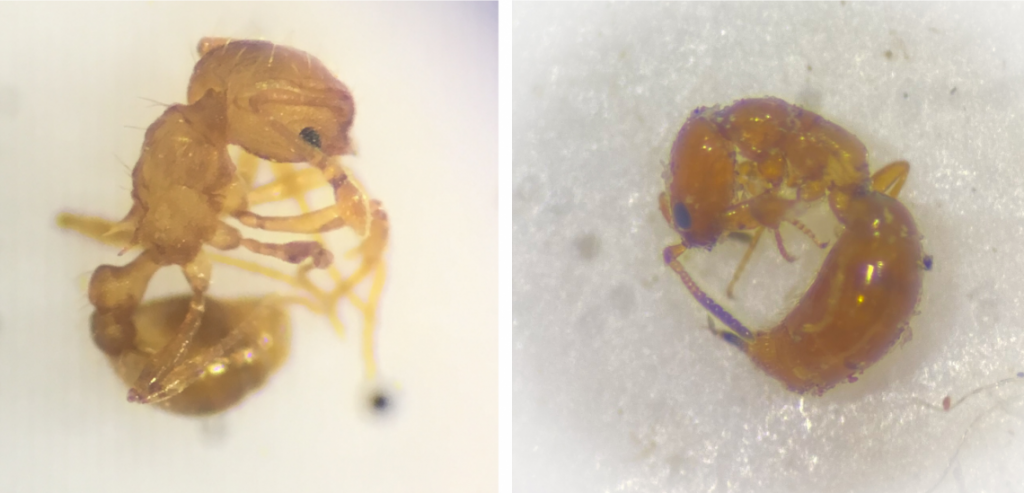

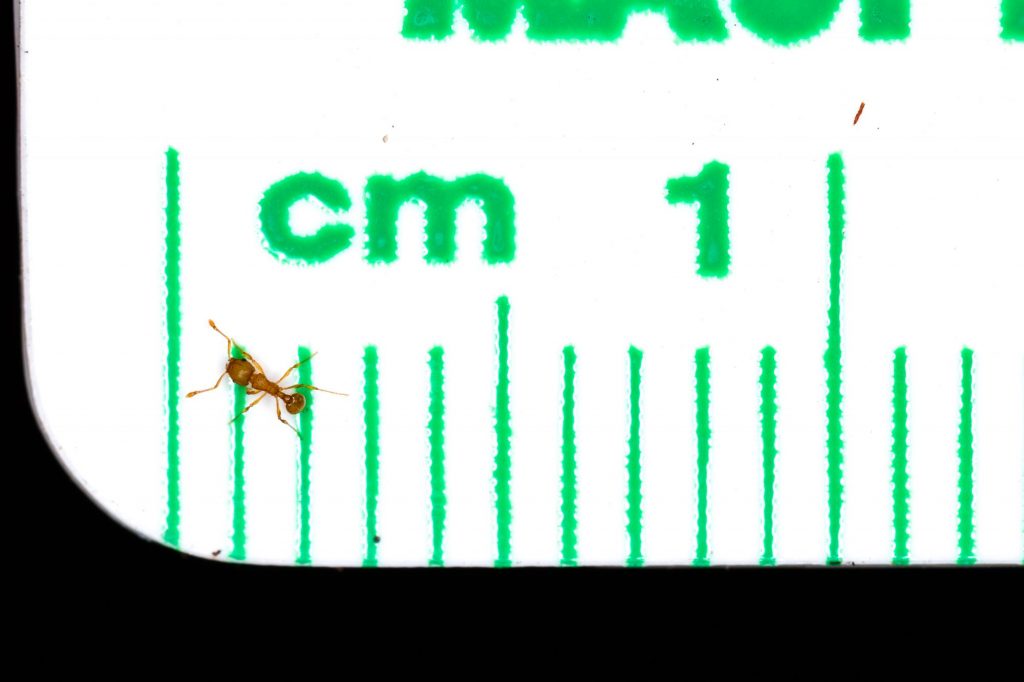

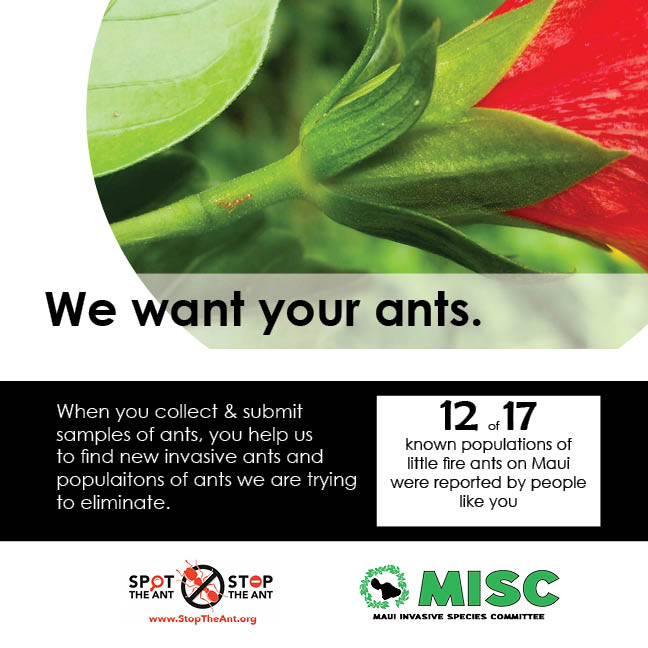

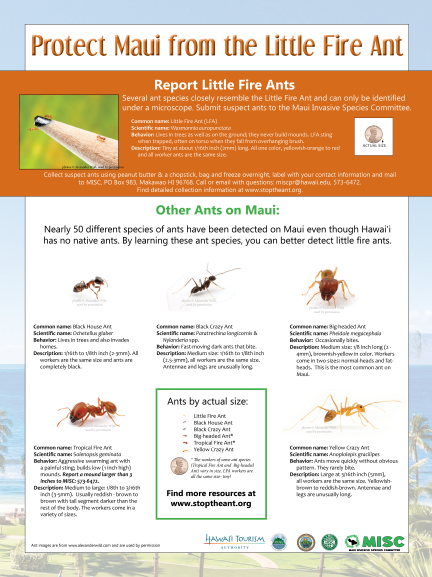

But it’s not just the plants themselves that can pose a threat. Pests and diseases hitchhike in plants and shipping materials and are carried long-distance. Inspectors with the State and Federal Departments of Agriculture check plants for unwanted pests and pathogens before and when they arrive in Hawaiʻi. A new program will help provide the tools for identification in the hands of growers as well as inspectors.

The Plant Pest Prevention Training is advanced training for growers to help them know what and where to look for hitchhiking pests. It also includes the steps they can take to stop these species. Covering everything from murder hornets to coconut pathogens, the goal of the program is to build capacity for detecting these problems early. By increasing the number of trained eyes out there looking, the Plant Pest Prevention Training provides additional layers of protection against hitchhiking pests. Information regarding pest distribution can help with purchasing decisions.

Developed with grant funding through the USDA Plant Protection Act 7721, the training will be launched and offered by staff at the county-based Invasive Species Committees to interested nurseries this year. Just like the Pono Endorsement program, participation is voluntary for this training.

As you make your plant purchasing choices this growing season, ask your vendors if they are aware of Plant Pono and the tools offered to nurseries. Visit plantpono.org to learn more.

Serena Fukushima is the public relations and education specialist for the Maui Invasive Species Committee. She holds a bachelor’s degree in environmental studies and a graduate degree in education from the University of Hawaii at Manoa. “Kia’i Moku, Guarding the Island” is written by the Maui Invasive Species Committee to provide information on protecting the island from invasive plants and animals that threaten our islands’ environment, economy and quality of life.

This article was originally published in the Maui News on March 12, 2022 as part of the Kia‘i Moku Column from the Maui Invasive Species Committee.

Read more Kiaʻi Moku articles