In 2009, Waihee farmer Christina Chang was stung on the eye by a tiny ant at her home on Maui. She suspected, and the Hawaii Department of Agriculture confirmed, that this ant was the little fire ant, Wasmannia auropunctata, never before found on Maui. The detection spurred creation of a new documentary, Invasion: Little Fire Ants in Hawaii.

In 2009, Waihee farmer Christina Chang was stung on the eye by a tiny ant at her home on Maui. She suspected, and the Hawaii Department of Agriculture confirmed, that this ant was the little fire ant, Wasmannia auropunctata, never before found on Maui. The detection spurred creation of a new documentary, Invasion: Little Fire Ants in Hawaii.

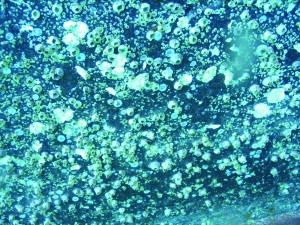

Invasive species introductions to Hawaii often end in regret and a list of should-haves. This film, produced by the Maui Invasive Species Committee, aims to change the result of the arrival of little fire ants in Hawaii. Featuring videography from award-winning film makers Masako Cordray and Chris Reickert, this half-hour film examines the biology, impacts, and potential solutions to the spread of little fire ants through interviews with scientists, farmers, and community on the Big Island reeling from the impacts of this miniscule, but devastating, ant. Viewers will learn how to identify and report new infestations, helping to protect Hawaii from this small stinging ant

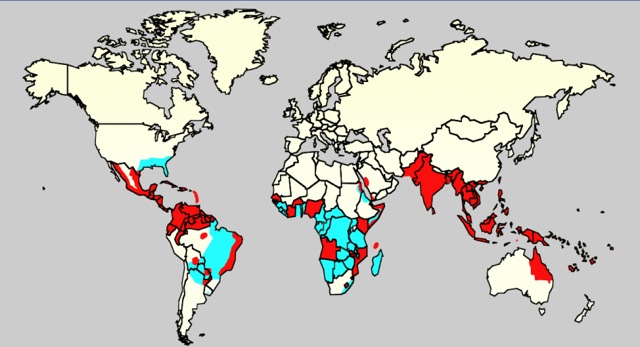

The Waihee site is on target for eradication. However, little fire ants have recently been detected moving between islands, raising concern about the establishment of new infestations. On Hawaii Island, the little fire ant is now widespread in the Hilo area where efforts are focused on educating landowners about control options. Infestations are now occurring on the Kona side as well. Research on effective control continues by the Hawaii Ant Lab, a joint project of the Hawaii Department of Agriculture (HDOA) and University of Hawaii. The little fire ant on Kauai is contained within a 12-acre area under active control by HDOA

The film will premiere on Maui January 8th at the McCoy Theater at the Maui Arts and Cultural Center. Doors open at 5pm. An awards ceremony and panel discussion will follow the screening. Food and beverages are available for purchase on site beginning at 4:30pm.

Screenings on other islands will follow. Please RSVP to miscpr@hawaii.edu to reserve a seat. Below is the current screening schedule:

- Maui: January 8, McCoy Theater and the Maui Arts and Cultural Center, 5pm

- Oahu: January 13, Cafe Julia at the YWCA, 1040 Richard St, 4:30pm

- Kauai: January 18, Kauai Community College Performing Arts Center

- Hilo: TBA (February 18)

- Kona: February 19, Aloha Performing Arts Center, 5pm

The film will also air throughout the state on KITV

Sat 1/11 630-7PM

Sunday 1/12 9-9:30AM

Sat 1/19 4-4:30PM

Sunday 1/20 10:30-11P

Funding and support for the film was provided by the Hawaii Department of Agriculture, County of Maui-Office of Economic Development, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Hawaii Community Foundation-Pikake Fund, Maui Electric Company, Alexander and Baldwin Foundation, Tri-Isle RC&D. MISC and the Hawaii Ant Lab are collaborative projects of the Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit.