Date: November 19, 2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASEContact: Lissa Strohecker, Public Relations and Educational Specialist Maui Invasive Species Committee PH: (808)…

Read More

MISC Target Species

Coqui frogs negatively affect the environment in more ways than one

In the dark, Darrel Aquino turns off the pump engine – the silence is a stark contrast to the noise…

Read More

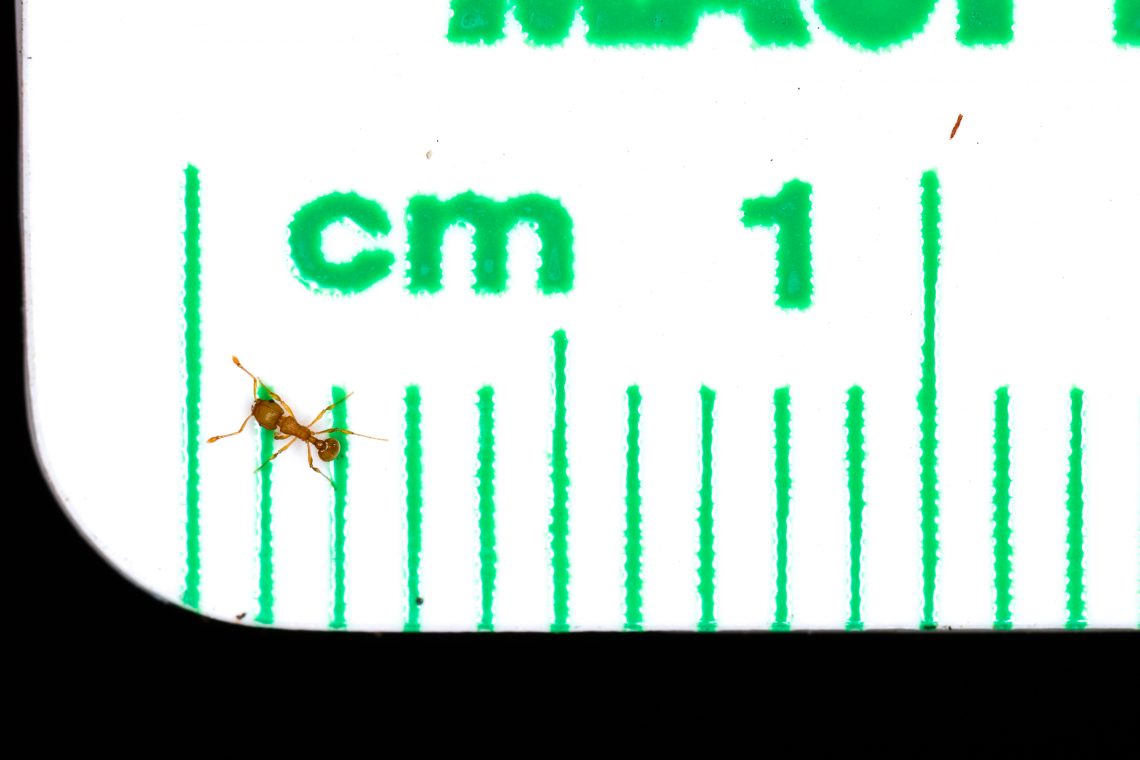

The little fire ant (LFA) has been detected on the campus of Lahainaluna High School

Date: May 05, 2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASEContact: Lissa Strohecker, Public Relations and Educational Specialist Adam Radford, MISC Manager, Maui Invasive Species…

Read More

The little fire ant (LFA) has been detected in the Twin Falls area, Huelo, Maui.

An infestation of little fire ants (LFA) has been detected at an area known as Twin Falls, in Huelo, East…

Read More

Press release 9/23/19: New infestation of little fire ants found in Waihee Valley

In late August 2019, a Waihee Valley resident called the Maui Invasive Species Committee (MISC) to report stinging ants. She…

Read More

Why All the Talk About Eradication?

Life in paradise inevitably means dealing with invasive species in some form. From termites to rats, centipedes to garden weeds,…

Read More