Each year over ships make over 1000 trips to Hawai‘i. Container ships and barges, fishing boats, cruise

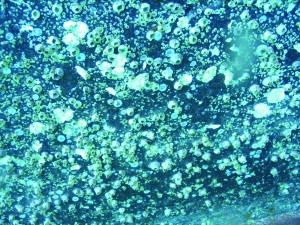

Organisms colonize an anchor chain. Photo courtesy of Hawaii DLNR-DAR

ships, and sailboats, aircraft carriers and military ships come bearing cargo for Hawai‘i or stop over on their way across the Pacific. Any of these boats could carry tiny stowaways from distant places, and that has resource managers concerned. Even an interisland boating trip could translate into trouble for your local reef.

“The majority of Hawai‘i’s aquatic invasive species came in via ballast water and hull-fouling,” explains Sonia Gorgula, the state coordinator recently hired by the Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources’ aquatic division to address the problem. Ballast water is taken by ships at sea or in port to maintain stability, and can contain organisms or larvae that may be harmful when released into a new environment, oftentimes thousands of miles from where they originated. Hull-fouling, or bio-fouling refers to the plants and animals that grow on any aquatic vessel, be it ship or yacht, dingy or dock. When these living organisms reach new waters, they can cause problems.

Of the two types of marine contamination, Gorgula says biofouling is the bigger worry in Hawai‘i. One species introduced this way is snowflake coral, a fast-growing soft-coral from the Caribbean. Since arriving in Hawaiian waterways, it has devoured the zooplankton that supports the marine food web and destroyed numerous black coral colonies. Hypnea, the rank invasive algae that washes up on Maui beaches, spread between the Islands attached to the underbelly of a fishing or sailboat. Hypnea is not only stinky and expensive to deal with on the beach, it outcompetes native limu.

Biofouling happens on any type of vessel, ocean or freshwater, that remains in port or dock long enough for organisms to become attached. “Broadly speaking it’s mussels, algae, barnacles,” says Gorgula. “When you start to see an assemblage become quite dense, you can even find crabs.” Boats function as floating reefs, transporting these aquatic aliens to Hawai‘i, where they may or may not find a home.

“Some species arrive and establish, then fail. Yet many species become invasive here that were not thought to be invasive until they get here,” says Gorgula. “Often there’s not enough information to predict what will become invasive.” One way to approach the situation is to treat all biofouling as harmful and focus on prevention—keeping boats with Hawai‘i on their itinerary free of small stowaways.

Biofouling is a drag, literally. Barnacles colonize the hull of a ship and reduce fuel efficiency as well as pose a risk of becoming invasive. Photo courtesy of Hawaii DLNR-DAR

Most commercial ships have incentives to keep hulls relatively free of growth; biofouling creates drag that reduces fuel economy. But other hidden “niche” areas underneath the boat—propellers and intake pipes used to pull in water for cooling the engine and fire-fighting—often house alien species. Cleaning the hull is part of regular boat maintenance; focusing on niche areas will help prevent the spread of hitchhikers. Certain paints are designed specifically to discourage fouling, and hidden spots can be painted as well as hulls, simple steps that feed into regular maintenance.

Policies and regulations for ballast water are well established worldwide, but biofouling has only received attention of recently. One of Gorgula’s tasks is to develop policy to protect Hawai‘i. “The biofouling policy issue is complex,” she says. “Around the world, only California, New Zealand, and Australia have developed policy. Globally, there aren’t many people working on it. We’re forging new territory” In 2007 the state legislature approved rules requiring ships planning to release ballast water to exchange the water first in the open ocean more than 200 nautical miles out to sea, reducing the likelihood ballast water will contain organisms that could find safe haven in Hawai‘i

It may seem trivial n a world of big ships and global transportation, but paying attention to the details can

A diver inspects a propeller for biofouling. Photo courtesy of Hawaii DLNR-DAR

make a big impact. Every boat, even those going interisland can help stop the spread of invasive aquatics. “Clean off biofouling in the same port where it accumulated,” says Gorgula. Be sure to clean your hull, anchor, props, bilge compartment, and any associated gear in the same watershed to prevent its spread to other watersheds and islands.

By Lissa Fox Strohecker. Originally published in the Maui News, January 13th, 2013 as part of the Kia‘i Moku Column from the Maui Invasive Species Committee.

You can find all the articles in the Kia‘i Moku series http://www.hear.org/misc/mauinews/

The Maui Association of Landscape Professionals, Maui Invasive Species Committee, and the County of Maui will recognize a professional landscaper, plant provider, or commercial/agricultural property owner’s efforts to protect Maui County from invasive species.

The Maui Association of Landscape Professionals, Maui Invasive Species Committee, and the County of Maui will recognize a professional landscaper, plant provider, or commercial/agricultural property owner’s efforts to protect Maui County from invasive species.